Marquette Bottling Works – part 1

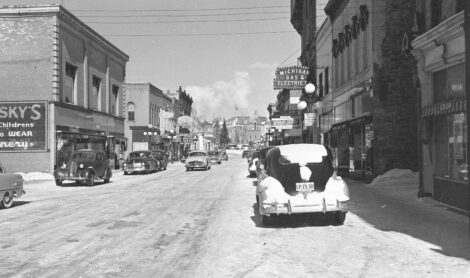

The Marquette Bottling Works at 117 N. Third Street, circa 1910 while it was owned by Frank Frei. The man on the left in white overalls is Joseph C. Stenglein Sr. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

A recently unearthed pop bottle with the name and image of Chief Kawbawgam sparked an interest in the early years of Marquette Bottling Works, which produced the commemorative bottle.

Although Marquette Bottling Works was not the first local company to combine carbonated water with sweetened syrups to create the popular fizzy drinks, it was certainly the longest lasting. On April 23, 1886, Henry Hoch and Arthur Heinemann announced that they had purchased the bottling works from Meeske and Hoch’s brewery and would be bottling and delivering both beer and carbonated waters.

A year later, on June 11, 1887, they revealed plans for a new building to be located at 117 N. Third Street. The company that came to be known as Marquette Bottling Works continued at that location until the post office expanded in 1962 and remained an independent business in Marquette until it was acquired by Pepsi-Cola in 1989, more than 100 years after the firm was founded.

Local historian and bottle collector Bill Van Kosky has found old soda bottles from more than 20 different Marquette County bottlers dating from 1868 to 1920. The large number of bottlers is an indication of how relatively simple it was to get into the soda business. Henry Arola of Republic, for example, began mixing carbonated soft drinks in his basement to serve friends and family after a sauna. He progressed to selling the drinks to supplement his mining income and eventually turned it into a business holding the local 7-Up franchise and bottling more than eighty cases per hour.

In Marquette, Henry Hoch was selling a wide variety of soft drinks from his bottling plant on Third Street. One advertisement from 1894 offers “ginger ale, orange cider, egg soda, birch beer, rocaurie, strawberry, celery phosphate, grapelette, champagne cider, selters water, iron and sarsaparilla, lemon soda, sarsaparilla, sherbet, wild cherry wine, and all leading temperance drinks.”

Although combining carbonated water with syrups and flavorings was neither particularly complicated nor expensive, getting those drinks to consumers was another matter. In the eastern U.S. states, soft drinks were initially sold predominately at soda fountains, generally located in drug stores. As one author noted, “It was healthy, refreshing, and demonstrated one’s temperance.” Outside of the northeast, however, soda makers bottled their drinks in glass bottles, where the beverage was more likely to be known as “pop” from the sound made when the bottle was opened.

Glass bottles, which were hand blown until the 20th century, were far more expensive than the ingredients in the drinks themselves. Local bottlers ordered their bottles from glassmakers located in areas where a supply of natural gas provided the intense heat necessary to make glass. To identify their bottles and reduce the chance that competitors would steal them, soak off the paper label, and either reuse them or sell them for scrap, bottlers ordered their bottles embossed with the name of the bottler. Even so, a bottler was fortunate if a bottle could be returned, washed and reused three times.

Beginning in the early 1900s, Marquette Bottling Works used a glass maker in Terre Haute, Indiana, the Root Glass Company, famous for inventing the classic Coca Cola bottle. Root was a pioneer in glass manufacture, and beginning in the mid-1910s, was able to move away from mouth-blown production to much more efficient machines. This, of course, was a boon for soda bottlers. But there was another development that was even more important–the rise of the temperance movement and the beginning of Prohibition.

As noted above, Henry Hoch was advertising soda as a temperance drink as early as 1894. Around that same time, he moved away from Marquette and the bottling works were purchased by Frank Frei, the son of German immigrants. In contrast to both his predecessor, Henry Hoch, and his successor, Matt Hirvonen, it appears that Frei did not do much to advance the business, dropping the advertising from both The Mining Journal and the city directory. But he kept the business going, and shortly before he sold it in 1919 added new bottle-washing machinery, since the cleanliness of the reused bottles was always a concern, and a new fully automatic bottling machine.

Michigan was known as “the first state in and the first state out” of Prohibition. In 1916, voters approved a ballot measure to ban the sale of alcohol everywhere in the state. The law became effective in May 1918, almost two years before the January 1920 effective date of the 18th Amendment. Although the Michigan law was not particularly effective, given that liquor was easily available in neighboring states, there was no doubt that change was happening, with Congress ratifying the 18th Amendment in January 1919.

Marquette Bottling Works changed hands in April 1919. That was an auspicious month to purchase a bottling works that bottled only non-alcoholic sodas. Matt Hirvonen, previous owner of the Gwinn Bottling Works, was the smart investor who purchased Marquette Bottling Works from Frank Frei.

Next week’s article will discuss more fully the relationship between Prohibition and soda sales and the remarkable growth of Marquette Bottling Works under Matt Hirvonen’s leadership. There may even be more about that Kawbawgam bottle.