The great Seney fire

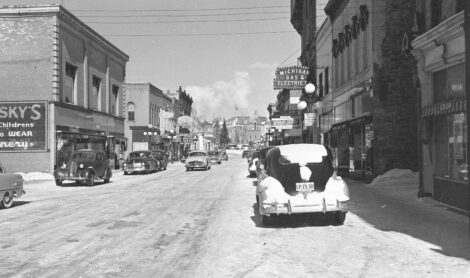

Pictured is the Seney fire of 1976. (Image courtesy of Greg Lusk)

The Walsh Ditch Fire is officially named for the closest landmark to the ignition point. More commonly known as the Seney Fire, it was sparked by a dry lightning storm on July 30, 1976. The next day a Michigan Department of Natural Resources aerial patrol spotted the blaze within the Seney National Wildlife Refuge. The Refuge Manager thought no action could be taken on the fire since it was in a congressionally designated “wilderness” area.

A chaotic response and inaction allowed the fire to grow to 1,200 acres in almost two weeks before any suppression action took place. Several weeks after the initial report, the fire “blew up,” spreading out of the wilderness and off the refuge onto state and private land. All told, the fire spread over 72,500 acres during a period of record drought, requiring an interagency firefighting force of more than 1,200 firefighters from twenty-nine states to achieve containment. It burned until the winter snow extinguished it.

Data gathered from the Marquette National Weather Service (NWS) station show a drastic departure from historic conditions. From 1872, the station’s establishment, there were no drier summers on record prior to 1976. The average summer rainfall for June, July, August, and September at the Marquette NWS is 12.79 inches. In 1976 only 4.79 inches were recorded, a deficit of eight inches, with only half an inch falling in August. Similar readings were reported throughout the Upper Peninsula. The protracted extreme drought during the summer and fall of 1976 allowed the fire to burn deeply in the Seney swamp, often entirely consuming the upper organic layers of soil.

The resulting “ground fire” literally meant the ground was burning. While not as spectacular as fast-moving surface or crown fires, they can do long-term damage to the forest and can be extremely difficult and costly to extinguish. Fires of this type may leave nothing but bare rocks with a thin skin of mineral soil in their wake. Conditions at Seney were comparable to the historic fires at Peshtigo (Wisconsin) and the Great Michigan Fires (Lower Michigan) in 1871 that burned millions of acres and killed thousands of people.

The terrain, soils, and vegetation caused numerous problems. The organic soils, a combination of peat and muck, sometimes several feet deep, were burning on and beneath the surface. There were pools of water, streams, and small rivers with areas of marsh grass interspersed with ridges and islands of pine, hemlock, spruce, ash, and birch. Most of the land did not lend itself well to travel, even by four-wheel-drive vehicles. Access, in many cases, was only by high-flotation-tracked vehicles.

There was a continuous struggle on the fire line by personnel and equipment to prevent further acreage loss. Fire line construction through the wetland was difficult, at best. The crews had to dig down to the mineral soil layers, removing deadwood and any roots that were burning like a fuse to unburned fuel on the other side of the line. Once the lines were built, they were burned out in an attempt to remove unburned fuel from the path of the oncoming fire.

Despite all the sophisticated equipment, any fire is, in the end, put out by people with tools, from shovels and pump cans to bulldozers and helicopters. Twenty-two agencies provided federal and state firefighters that came from twenty-nine states representing all corners of the country, from Alaska and California to Georgia and Maine, to join the fight.

Many MDNR forest firefighters and specialists were pressed into service from all around the state and performed admirably, but being professionals in their field, this came as no surprise. The unknown factor in this critical situation were the many Department of Natural Resources staff members who became involved despite having never logged a single hour on a forest fire. They were Fisheries and Wildlife Biologists, Park Rangers, Foresters, Surveyors, Waterways, Geologists, and more than a few men and women who were normally anchored to a desk. Mechanics from around the state, normally surrounded by the conveniences of a repair shop, packed their toolboxes, and performed heroics to keep the firefighting equipment in good working condition.

It was exhausting work, but the fire was contained through the combined efforts of the more than one thousand state and federal firefighters, cooperators, and support staff that responded to the challenges of suppressing the largest fire in Michigan since 1908. Their remarkable effort stands out as an example of what dedicated professionals can do together as a team.

The fire was abandoned when heavy winter snow finally blanketed the Upper Peninsula. The following spring, the snowfall thawed, finally extinguishing any remaining smoldering organic soils that burned as deep as eight feet beneath the surface. The final cost estimates for fire suppression were over $8,000,000 with over $1,000,000 from the state, plus timber damage and regeneration costs. The total suppression cost today would exceed $40 million, adjusted for inflation.

To learn more about this historic fire, don’t miss The Great Fire of Seney presented by the Marquette Regional History Center on Wednesday, March 27 at 6:30 p.m. Gregory Lusk, author of the recently self-published book, The Great Seney Fire: A History of the Walsh Ditch Fire of 1976 will speak. Hear details and stories of the incident from Lusk, the assistant fire boss for this event. $5 suggested donation. For more info visit marquettehistory.org or call 906.226.3571.